The Social Dynamics of Technological Substitution

Back in 2007 and after several annual trips as a visiting PhD student to MIT Sloan School of Management, I published a theoretical article with my co-author Henry B. Weil. We proposed an integrated model to better apprehend the dynamics of social factors in technological substitution.

Traditional models of technological diffusion, particularly those rooted in an epidemic structure, have long relied on the Bass model and its variants to forecast adoption. While these frameworks offer a robust fit to historical data, they often assume a simplified decision process, uniform criteria across adopters, and a fully interconnected social structure. By challenging these underlying assumptions we suggested that the dynamics of technology adoption are not merely passive diffusion, but rather a complex substitution process involving obsolescence, vested interests, and profound social struggles.

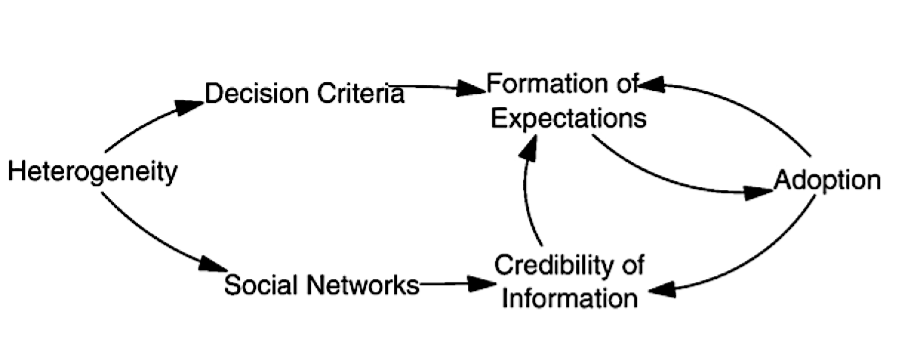

Our integrated framework indicates that the success of a paradigmatic shift is contingent not only on technological characteristics but, crucially, on managing deep-seated social dynamics and heterogeneity. To fully grasp substitution patterns, we must shift our analysis to multiple levels of granularity, moving from individual cognition to aggregated social topology. The process of technology adoption includes recursive interdependencies between demand heterogeneity, decision criteria, the formation of expectations, the topology of social network, and the credibility of information.

If you are interested in listening to an audio description of our integrated framework on the dynamics of social factors in technological substitution, please check the podcast below (by NotebookLLM). Also available on my Soundcloud page.

I. The Micro-Level: Individual Cognitive Processes

Understanding collective market behavior must begin with the individual decision-maker. We mobilize concepts from cognitive psychology and the principles of decision-making under uncertainty to establish a theoretical basis for how external reality is perceived and how expectations are formed.

Personal Constructs and Uncertainty Reduction

Individuals operate via a system of personal constructs—mental models or habitus—which channel their psychological processes and shape how they anticipate events. Novelty inherently challenges this established system. For the potential adopter, the innovation decision process is fundamentally an exercise in uncertainty reduction.

The perception of novelty introduces high levels of risk (both technological and market), which can be experienced as anxiety or threat when the events fall outside the system’s “range of convenience.” Adoption is thus not merely a utility calculation, but an evolving process to assimilate new information and reduce perceived risk, influencing decision criteria over time.

The Dynamics of Expectations Formation

Individual adoption decisions are often grounded in the Subjective Expected Utility (SEU) model, where the marginal utility of adoption is evaluated against a reference point. However, the perception of a technology’s trajectory generates dynamic expectations that can produce systematic and predictable errors.

Our analysis shows that if potential adopters use a simple linear extrapolation of the recently perceived improvements to form expectations about the technology’s future performance at a forecasting horizon, then different social dynamics emerge across distinct market phases:

Underestimation (Early Caution): In the nascent phase, the slow initial rate of improvement is linearly projected, leading to a cautious underestimation of the technology’s long-term potential. Early adopters may be slow or hesitant due to this perceived lack of momentum.

Enthusiasm and Option Value of Delay: As the technology enters the steep portion of the S-curve, the high perceived rate of improvement creates positive surprise and enthusiasm. This acceleration in perceived value creates a significant option value of delaying adoption, as users rationally anticipate much greater performance in the near future. This perceived gain is counterbalanced by increasing opportunity costs (e.g., loss of competitive advantage or accumulating knowledge discrepancy) that accrue during the waiting period.

Overshooting and Disappointment: As the technology approaches its performance asymptote (due to diminishing returns), the linear extrapolation model continues to project rapid growth, leading to expectations that become largely unrealistic. This overshooting creates a phase of widespread disappointment when actual performance fails to meet inflated expectations, often leading to a search for alternative solutions.

These dynamics demonstrate that individual cognition generates internal market fluctuations that complicate the smooth, logistic trajectory.

II. The Meso-Level: Market Heterogeneity and Criterion Shift

Moving to the aggregated level, population heterogeneity is structured by three interrelated dimensions: personal constructs, segment-specific valued functionalities, and, most critically, shifting decision criteria across adopter categories.

Based on the attitude towards risk, the market population is stratified into established categories who will adopt the technology at different times: Innovators, Early Adopters, Early Majority (Pragmatists), Late Majority (Conservatives), and Laggards. The critical challenge for a successful substitution is the fundamental change in the primary evaluation metrics across this life cycle.

The Systematic Shift in Decision Focus

Moreover another important change occurs as the technology diffuse over time and across adopters categories. The focus of the technology adoption decision systematically shifts, pivoting from abstract technological merit to concrete, risk-mitigating market factors:

Early Market (Innovators/Early Adopters): This segment is characterized by permeable constructs and cosmopolitan (horizontal) communication patterns. Decisions are dominated by the intrinsic Technology Characteristics and expectations of Future Performance. They are comfortable with high uncertainty and value the technology for its potential and functional merit.

The Chasm and Mainstream Focus: The challenge of “crossing the chasm” stems from the shift to the Early Majority (Pragmatists). This segment has vertically-oriented, risk-averse networks and is driven by a strong sense of practicality. Their criteria fundamentally change from what the technology can do to how safe it is to adopt. Decisions shift toward tangible proof points:

Product Credibility: Evidence of quality, robustness, and stability.

Company Credibility: Focus on vendor reputation, strong support infrastructure, and longevity.

This strategic transition requires change agents to pivot their focus from pure R&D and technological advancement to the establishment of market validation, credible reference accounts, and robust infrastructure.

III. The Macro-Level: Social Topology and Critical Mass

Traditional diffusion models assume that the system of interpersonal communication is fully connected and that word of mouth (WoM) is a uniformly influential force. This neglects the realities of social topology—the structure of the interpersonal networks that mediate information flow.

Non-Uniform Communication and the Discounting Effect

The structure of interpersonal networks is non-uniform; communication frequency is not constant across the social structure. Furthermore, the relevance and credibility of the information generated are deeply affected by the heterogeneity of decision criteria.

WoM Quality over Quantity: WoM is not a simple cumulative volume. Its effectiveness is a function of the source’s prestige and the message’s relevance to the receiver’s dominant decision criteria.

The Discounting Mechanism: Early adopters, focused on technological merit, communicate primarily through horizontal channels. When this WoM is received by the mainstream market, whose primary criteria are risk and credibility, the message is often discounted. The source (the enthusiastic innovator) may be perceived as a “whiz” or “deviant” by the risk-averse pragmatists, causing the message to be filtered as irrelevant “technology hype” and actively delaying adoption.

This discounting effect prevents the raw volume of accumulating WoM from reaching the critical mass necessary for self-sustainable diffusion.

The Strategic Role of Opinion Leadership

Social topology singles out certain individuals as opinion leaders or reference users due to their institutional weight or prestige. A small number of influential adopters represents a much stronger critical mass than a larger number of adopters lacking influence.

Our system dynamics model then demonstrates that when early adopters lack this opinion leadership, the substitution pattern can exhibit step-like behavior or waves, where the mainstream delays adoption until a credible information threshold is achieved. This highlights the managerial necessity of targeting influential, referenceable customers who can generate WoM that is perceived as relevant and credible by the mainstream.

Conclusion and Managerial Implications

Our integrated framework—linking individual cognitive processes and heterogeneous decision criteria to the structure of social topology—provides a more comprehensive understanding of complex substitution patterns than reliance on simplified logistic models.

A critical managerial objective is to form more realistic expectations and mitigate the risks associated with market misreading:

Avoiding the False Negative Error: The initial decline in sales after the enthusiast phase may not signal a failed launch but merely the period during which discounted WoM slowly accumulates toward the critical mass. Abandoning the technology too soon risks a false negative error.

Mitigating the Double Shift Risk: Overconfidence in a logistic substitution trajectory can expose the firm to a “double shift,” where early adopters who are already involved in a shift to a new technology (n+1), then move directly to a third, emerging technology (n+2) before the critical mass for the new technology (n+1) is attained, thereby cutting off WoM and stranding the (n+1) firm.

Successful technological substitution demands that change agents evolve their strategy to match the shifting social focus, prioritizing the cultivation of credible, influential references over mere sales volume in the early stages.

The full paper is available here.

Dattée, Brice, and Henry Birdseye Weil. “Dynamics of social factors in technological substitutions.” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 74.5 (2007): 579-607.